Arijeet Ghosh

Sai Bourothu

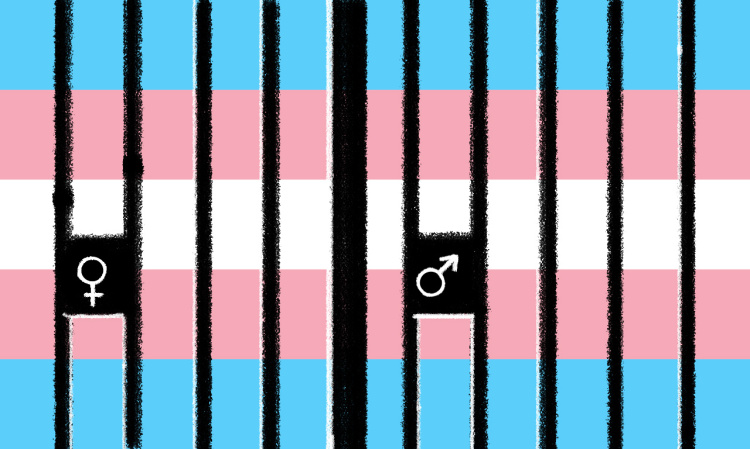

In response to a recent petition before the Delhi High Court, the Central Government through the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) and the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has submitted that it intends to include ‘transgender’ as a category in the gender classification of prisoners. The NCRB stated that from Prison Statistics India (PSI)-2020 and onwards, prisoners will be classified as ‘Male’, ‘Female’, and ‘Transgender’ in the PSI proforma and annexures, and directions have been issued to the Director Generals’ (DGs) of all prisons across the country for collection of data as per the above-mentioned gender classification. Further it also informed that it was also planning to conduct a two-day online “Training of Trainers for Prison Statistics in India”, in which special sensitisation will be carried out about the inclusion of ‘transgender’ as a gender classification.

Although a welcome step, the fact that such directions have been passed in the far end of 2020, i.e., almost six years after the decision of the Supreme Court of India in National Legal Services Authority v. Union of India (hereinafter, NALSA Judgment), raises serious concerns over the implementation of the landmark judgment. It is important to highlight this delay, as the NALSA Judgment laid down a basic framework enumerating the constitutional and legal rights of transgender persons, that needs to be protected. Amongst its directions, the rights which need mentioning are the right to self-determination of gender identity, the grant of legal recognition of the transgender identity, the establishment of transgender welfare boards, and the direction to both Central and State governments to initiate policy making around inclusion of transgender persons.

Additionally, in this abovementioned context, there is a need to further ask pertinent questions regarding the plight and the situation of incarcerated transgender persons before the passing of these recent directions by the Delhi High Court. How was the data on transgender persons being recorded before being remanded to prison? What was the identity ascribed to them while being admitted to prison? How were the search procedures carried out on admission and how were transgender persons placed inside the prison with the lack of explicit recognition of their gender identity? The focus of this article is to try and attempt to answer some of these questions.

Recognising Transgender Persons as a Vulnerable Category inside Prisons

The very nature of prisons in this country makes prisoners a vulnerable category on their own. This vulnerability can be attributed to multiple factors such as power imbalance between administrators and prisoners, curtailment of fundamental rights such as personal liberty and privacy, social stigma surrounding incarceration to name a few. However, there also exists an acknowledgement that certain groups of prisoners are more vulnerable than the others. Women, children, prisoners suffering from both mental and physical disabilities, foreign national prisoners are some categories that can be considered to be more vulnerable, given the intersectional impact of their identities, combined with vulnerability of being a prisoner.

However, one category of prisoners that has been largely invisibilised from these discussions are those who identify and belong to sexual minorities, such as lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI+) persons. Not only has the UN Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights recognised this vulnerability, but they have also further gone on to highlight the special vulnerability of transsexual and transgendered persons who are at a greater risk of both physical and sexual abuse from prison officials as well as fellow prisoners. This intersectional vulnerability has also been acknowledged by international organisations such as Penal Reform International as well as Association for Prevention of Torture, who further state that the vulnerability is not limited to detention settings, but can be seen throughout the different aspects of the criminal justice system. Hence, it is important to emphasise that just a legal recognition of identity of transgender persons in NCRB data is not enough. It needs to go beyond and gather data on the experience of LGBTI+ communities, and in particular, the transgender community while denoting and focussing on the specific vulnerabilities faced by them when incarcerated.

Specific Vulnerabilities: Admission Procedures and Transgender Prisoners

In a recently released report by Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI), there were an estimated 214 transgender prisoners confined inside the prisons in this country between the period of May, 2018 and April, 2019. One of the findings of the report highlights that there existed no proper mechanism or uniformity in the maintenance of data regarding transgender persons. This finding corroborates the fact that it is only recently that NCRB has directed the DGs to record the data of transgender prisoners. As a result, the report also remains sceptical about actual number of incarcerated transgender prisoners and states that the number might be much higher. This is highly probable, keeping in mind a recent news report from Gujarat, wherein it was found that the transgender prisoners in the State were being misgendered as ‘males’ due to the lack of column for transgender as a category in prison records.

Admission Procedures

Misgendering of transgender prisoners has a direct consequence on their treatment by prison officials during their admission to prisons. In general, a perusal of State jail manuals and the Model Prison Manual (MPM, 2016) suggest that the admission process includes recording of prisoner information, a thorough physical search, medical examination of the prisoner and allocation of wards within the prison. It is well recognised that transgender persons faced specific problems with the abovementioned admission procedures, as is evidenced by the Yogyakarta Principles & Yogyakarta Principles (YP+10). These universal principles, published as the outcome of an international meeting of human rights groups, impose a positive responsibility on the States to implement policies that ensure that transgender prisoners are treated with humanity in regard to body or other searches. It further mandates that transgender persons are allowed to participate in decisions regarding the facilities in which they are placed when in detention settings.

- Search Procedures

Amongst these procedures, in particular, the aspect of body searches becomes extremely relevant when it comes to transgender prisoners. While traditionally, prison manuals provide for male prisoners being searched by male staff and female prisoners being searched by female staff, a perusal of all State jail manuals and the MPM, 2016 indicate that there exists no policy which enumerates on search procedures being inclusive of the needs of transgender prisoners. Search procedures (including superficial checking and complete strip-search) can be particularly invasive and affect the dignity of transgender prisoners as can be evidenced through the following experience:

“ Even though we asserted continuously that we are transwomen, the prison officials stripped us. They poked and probed at our bodies and were visibly amused, while cracking jest among themselves, at the fact that we identified as transwomen. They did not let us wear back our clothes until we were utterly humiliated.”

KMV Monalisa, General Secretary, Telangana Transgender People’s Association

The fact that even after the self-assertion of identity of a transgender woman, invasive search procedures were carried out (including strip search), followed by the incidents of ‘jest’ and laughing at the bodies of transgender person, highlights the non-implementation of the NALSA Judgment. This is both in regard to right to self-identification as well as the fact that sensitization programmes regarding transgender persons (in particular, with prison officials) is not being carried out at State level.

- Medical Examinations and Placement Inside Prisons

Another crucial aspect of admission procedure that has a direct impact on transgender prisoners is that of medical examination followed by their placement within prisons. The CHRI report, which gathered data in this regard, highlighted that there existed no uniform policy for the placement of transgender prisoners. Different policies were in place across States which included placement based on gender mentioned in court warrants or placement based on the advice of the medical officer during medical examination. It is exactly the process based on the advice of medical officer which needs further scrutiny.

As the CHRI report states, majority of the prisons in the country placed transgender prisoners in the male/female ward based on the identification of their genitalia. The identification was done during the medical examination carried out by medical officer of the jail and based on whether the transgender person had a penis/vagina, they were placed in respective wards. This reduces both gender and gender identity to genitalia, which is violative to the experience of transgender persons. Further, this determination of gender identity through an inspection of genitalia, removes scope for negotiations of safety and comfort that the transgender person could avail through the self- determination of gender identity.

While most States did not have this procedure written down as law, NCT of Delhi was the only state which although identified transgender persons as a category of inmates with special needs, it through an official circular, laid down procedure for separation of transgender prisoners based on their genitalia. Not only is such practice in flagrant violation of the right to self-identification of transgender persons as recognised by the NALSA Judgment, butthe circular of NCT of Delhi can also be considered as standing in contempt. The violence and indignation suffered by transgender prisoners while undergoing such medical examination is evident through the following experience:

“When asked, I told them I am a transman. I have gotten my upper body operation and am on a monthly dose of testosterone. I have facial hair, and my voice is that of a man. The lady doctor asked me to strip, and when I refused, two prison officials forcefully undressed me. Everyone kept staring at my private parts and made fun of the stitches on my chest. They made me wear women’s clothes, and I had no access to testosterone shots. I wanted to kill myself, after seeing my body change while I was in prison.”

- Shakti (Name Changed), Transman

The above-mentioned experience by Shakti, not only further corroborates the problems posed by search procedures against transgender prisoners, but also the instance where he was forced to wear “women’s clothes” and being placed in a women’s ward despite identifying as a transgender man,evidences the kind of violence transgender persons can face inside prison, and more specifically, transgender men.

Furthermore, by being placed in wards which do not match with their self-identified gender, additionally increases the risk of physical, mental and sexual violence to which transgender prisoners can be subjected to.

“I am a transwoman, and I was kept in the male prison. I got through the medical examination because I hadn’t gotten any operations and I did not tell them anything about it. It was easier to pass through the prison officials and doctors, but the fellow prisoners realised within a few days of me being there. I have feminine features and I am used to referring to myself with she/her pronouns. Once they realised, it was a nightmare for me. They demanded sexual gratification day and night. Three men raped me, and I was bleeding. I was threatened to keep quite by the other prisoners, and they still kept asking me for sexual gratification. I had severe haemorrhoids with infection and puss, to an extent that I was unable to walk. I was taken to a doctor and then kept in isolation ward.”

- Kamala (Name Changed), Transwoman

The story narrated by Kamala is not a one-off incident. Her experiences bring back to memory the incident of sexual assault, harassment and rape of five transgender persons who identified as transgender women, but were kept the male wards of jails in Mysuru & Hassan in Karnataka, thereby bringing to life these lived realities.

Transgender Persons and Prison Services

While it can be appreciated that NCRB in its submissions to the Delhi High Court has informed that they intend to carry out sensitisation sessions with prison officials in regard to transgender prisoners, a larger question that needs to be asked is in regard to the recruitment of transgender persons in State Prison Services. However, since the NALSA Judgment of 2014, which directed the States to take steps to ensure reservation for transgender persons in public appointments, the CHRI report indicates that no transgender person has been recruited by any State in its prison services since 2014. This does not come as a surprise, keeping in mind the history of difficult litigations that the transgender community has faced when it has come to the recruitment of transgender persons in police services as well.

Way Forward

The above list of issues which transgender prisoners might face while incarcerated should be treated as an indicative list and not an exhaustive one. Issues like violence within prison settings based on the gender identity (from both prison staff and fellow prisoners) as well as the need to cater to specific medical needs of transgender prisoners are ones that need to be documented and explored further. It will also be important to note that apart from transgender and inter-sex persons, vulnerabilities of prisoners ascribing to non-normative sexual orientation (LGB Groups) also needs to be documented.

The submission made by the NCRB and the directions passed by the Delhi High Court is just the first step towards recognising the need for larger and systemic structural reforms for transgender persons inside prisons. As has been highlighted in this article, there is an immediate need to use this opportunity to advocate for further reforms that will be more inclusive of transgender persons. However, it needs to be kept in mind that to bring forward any reform, transgender persons need to be in the centre of such process, and no changes should be brought without effective consultation with the transgender community. As has been evident in the recent case of the passing of The Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2019, there is an attempt to pass laws without community consultation and portraying the government in the light of protector of transgender persons. Such an attempt made in bringing forth prison reforms for transgender persons, without consultations, is only going to lead to more resistance from the communities rather than acceptance of such reforms.

Sai Bourothu is a Bahujan Transwoman, criminologist and early career academic. She has been working in the areas of police and prison accountability research with a specific focus on Queer individuals/ communities in deprivation of liberty. Arijeet Ghosh is a Lecturer at Jindal Global Law School, O.P. Jindal Global University. Arijeet has keen interest in working on the intersection of Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.