Neetika Vishwanath in conversation with Jessica Jacobson

India has a record of prescribing and imposing harsher sentences in response to widespread protests against the country’s rampant sexual violence rates. Courts have continued to evoke its notions of public opinions to routinely impose death sentences on persons convicted for rape and murder. Recently, the legislative assembly of West Bengal passed a Bill introducing the mandatory death sentence, in response to widespread protests over a rape and murder that took place in Kolkata earlier this year. These responses from courts and lawmakers- designed to abate public anger and maintain legitimacy- begs the question: How far, if at all, should public opinion play a role in sentencing laws, and the decision making of a court in an individual case?

Project 39A’s Neetika Vishwanath (Director, Sentencing) speaks to Jessica Jacobson, Professor of Criminal Justice and (then) Director of the Institute of Crime and Justice Policy Research (ICPR) at Birkbeck, University of London, on public opinion about sentencing, and its influence in a court’s decision making, in this interview.

Neetika Vishwanath [NV]: Hi Jessica. Thank you for agreeing to talk to us. I have had the opportunity to engage with your prolific body of work on sentencing practices in the United Kingdom, and the public’s opinion about sentencing. But for the benefit of our readers, could you please introduce us to your research on sentencing?

Jessica Jacobson [JJ]: At ICPR, we carry out what we describe as policy-oriented, academically grounded research on many aspects of justice. We do research on policing, we do research on prisons and we do research on court proceedings. And my own special expertise and interest is in court proceedings.

As part of this, I have done research on sentencing which includes looking at public attitudes to sentencing. I have been involved in a number of studies which have been commissioned by the Sentencing Council and its predecessor bodies, the Sentencing Advisory Panel and Sentencing Guidelines Council, that examined what the public think about the sentencing of different kinds of offences or the public’s views on the principles of sentencing.

For example, we did work looking at public attitudes to the sentencing of drug offences, young offenders and overarching sentencing principles.

NV: While your empirical research focussed on public attitudes on sentencing, I wanted to start by asking you a foundational question about the role of public opinion at sentencing. My question is- should public demand for a specific punishment become relevant for a court when deciding a case? I ask this question because a strand of Supreme Court decisions, more so in the recent past, have approved the role of public opinion as a sentencing factor in death penalty cases. Besides, in serious homicidal cases that invite media and public attention, there is strong public demand for harsher sentences including the death penalty.

JJ: I would say no. Public demands for a particular sentence should not be relevant to any individual sentencing decision. Any individual decision should reflect the wider sentencing framework within which all decisions should be made. And that framework is likely to be made up of a mix of law – being statutes and precedents – and guidance.

NV: Right. But how would you respond to a situation where the law recognises public opinion as a sentencing factor? As I stated before, over the years, the Supreme Court of India has allowed public opinion to feature as a relevant sentencing factor in death penalty cases through the use of amorphous phrases like ‘collective conscience’ and ‘society’s cry for justice.’ What do you make of a sentencing law that recognises public opinion as a sentencing factor? Is such a component in the law misplaced?

JJ: It is not entirely misplaced. Certainly, I think the sentencing framework should, to an extent, be aligned with public opinion – or, at least, not be highly divergent from public opinion. In England and Wales, there was a view until the 1990s that public opinion was irrelevant to sentencing decisions, and should be irrelevant to sentencing decisions. Since then, there has been much wider recognition that there is a need for some alignment between public opinion and sentencing.

And why is that? Sentencing is done on behalf of the public. If there is too much divergence, it is less likely that people will have trust in the justice system or in the authorities. The system will not have legitimacy, and people will be less likely to comply with the law because they feel they should do so, rather than just because they fear consequences if they do not do so.

But the risk here is penal populism. When policy makers feel they need to follow public opinion, they might simply institute increasingly severe sentences. This is an experience we have had in England and Wales as well.

These changes do not necessarily provide the public with satisfaction over the law and sentencing. In fact, the public remain highly dissatisfied, partly because there is a real lack of knowledge and understanding of sentencing, and particularly a belief that sentencing is far more lenient than it is in reality. The real question then is: What does it mean to engage public opinion without following (presumed) public demands for harsher sentences? I think there is a way of constructively engaging with public opinion.

I do not think we do it very well in England and Wales yet. More can be done to ensure that the public are better informed about sentencing. Undertaking nuanced, sophisticated analysis and research of public opinion would mean that you are not only looking at the kind of top-of-the-head responses to questions about sentencing, but really looking at what the public would feel once confronted with a more detailed picture and understanding of what an offence and sentencing might involve. That kind of information should inform sentencing policy, rather than, as I said, slavishly following what are assumed to be public demands only for more severe sentences.

A large part of this requires encouraging more responsible, less sensationalist media reporting of crime. Often, it is what the media says about crime and about public demands that influences politicians.

NV: Right, thank you. Your point is well taken that the sentencing policy in some way needs to align with the public opinion in order to gain legitimacy amongst the public. But does establishing public legitimacy demand that courts sentence on the basis of their perception of the public opinion? I ask this specific question because it is common for court decisions in India across all levels of hierarchy to justify a harsher sentence because the public supports it. Courts rationalise this as a way to foster public confidence. The understanding is that going against the perceived public opinion and imposing the lesser sentence will betray the public confidence in the legal system. How would you respond to this line of reasoning? Does it raise any concerns?

JJ: I do not think the judiciary has a core role in bolstering public support for the criminal justice system. I think their core role is to uphold the rule of law; to adjudicate in decisions before the courts; and to a certain extent, manage the business of the courts.

One would hope that that role, when performed in an effective and humane manner, will lend greater trust in and support for the criminal justice system. That said, building trust is not the primary focus of the work of the judiciary.

Note: This interview has been edited throughout for clarity.

You can access Jessica Jacobson’s publications on prisons, fair procedures, and public opinion and sentencing here.

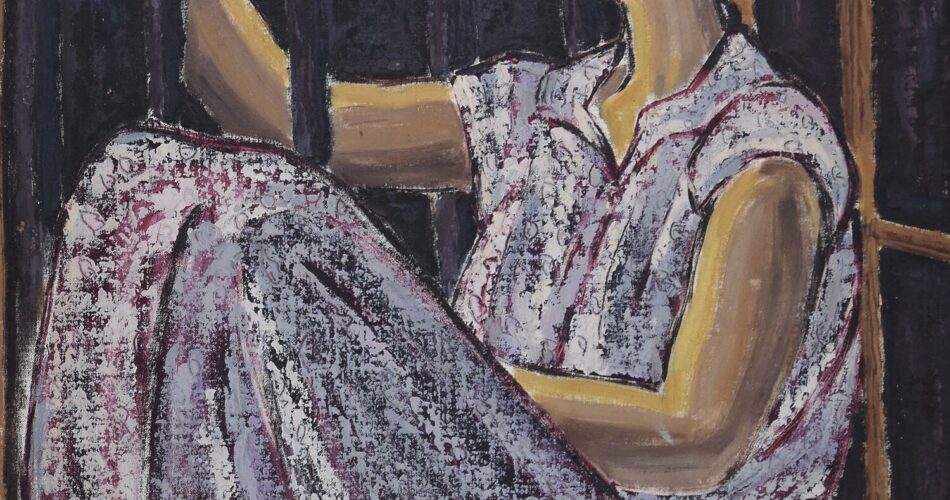

Artist featured: Inji Efflatoun (1924 – 1989) was one of Egypt’s most important visual artists. A pioneer of modern Egyptian art, she was also a leading feminist, anti-imperialist, and Marxist. The paintings featured in the post were created during her 5 years of incarceration in Egypt. Read more about her experiences in and of prison, and her perspective on creating art while incarcerated on MidEastArt.